To my teacher Late Mrs. Chitra Srinivas, Sardar Patel Vidyalaya, New Delhi.

The year 1910 was a relatively peaceful time in Indian history. King George V became king of England, while the effects of the Morley-Minto reforms continued to be felt with a greater role for native Indians in provincial and native legislative councils. Elsewhere around the world, Boutros Ghali, the first native-born prime minister of Egypt was assassinated, while Professor Robert Williams Wood published the first infrared photographs in the journal of the Royal Photographic Society. Also, the Earth passed through the tail of Comet Hailey.

Young Rakhaldas Bandyopadhyay was oblivious to most of these events as he boarded the steam locomotive from Howrah Junction destined for Allahabad and then on to Delhi. He felt the sharp edges and the raised seal of the letter appointing him as junior archaeologist with the Archaeological Survey of India. The letter bore the impressive signature of Director General, Sir John Marshall. In fact Sir John had been instrumental in hiring native Indians within the Archaeological Survey, and Rakhal was to be one of the first natives appointed to a senior technical position. As the steam train moved briskly through Bordhoman district (of Bengal), Rakhal pondered over his own interests and possible oncoming challenges. As a student in the MA History class of University of Calcutta, he had developed a keen liking for 19th century Indian history, much to the chagrin of some of his fellow students and most of his professors. The latter were loyal subjects of His Majesty the King of England, and thus felt obligated to focus only on the glory of the crown. Rakhal was especially interested in the last days of the Mughals, if given a chance he would possibly write a doctoral dissertation on the same. He did not know what the Survey had in store for him. He could even be shipped off to a far land to dig up some glorious artifacts for the gratification of the crown, and all its numerous royals and ministers. He looked around the first-class cabin and observed the smattering of Englishmen and few Sikh businessmen all naturally drawn in their own thoughts, few paying any attention to the dusty outdoors. “No one has a clue”, Rakhal thought, “to all the secrets that could be hidden in these outdoors. Great secrets of an ancient land…none beholden to any crown or empire.”

As the train reached Delhi, Rakhal felt a surge of excitement on being able to see the old city. It was possibly his love for  history that had changed the parochial worldview so typical of many educated Bengali bhadralok (gentlemen). “If only they understood”, pondered Rakhal while waiting for the tongeywalla (horse-drawn carriage driver) to load his luggage, “that all the different peoples of India have unique achievements in their own way.” The carriage ride took him through the bustling streets of the old city, gleaming with the late-autumn celebration of the festival of lights so prevalent in these parts. The smell of sweets laid open under cloth canopies cloaked with the aroma of oil burning in small clay lamps to create an uniquely appetizing journey. His temporary accommodation was very close to the old city, much to his delight. In those first weeks of November 1910, Rakhal added the love for sweets to his passion for history. At the Survey, he also became acquainted with many who did not care much for either. There was Coomaraswami, a small quiet man with a sharp wit, who worked in the preservation of manuscripts, but who was really interested in becoming a civil servant. There was Rai Bahadur Daya Ram Sahni, whose impressive knowledge of architecture was surpassed by his grand wealth, and his ability to remain humble in spite of both. And there was Kripal Singh, head of the transport section, with a mysterious smile that disappeared as quickly as he did when on assignment.

history that had changed the parochial worldview so typical of many educated Bengali bhadralok (gentlemen). “If only they understood”, pondered Rakhal while waiting for the tongeywalla (horse-drawn carriage driver) to load his luggage, “that all the different peoples of India have unique achievements in their own way.” The carriage ride took him through the bustling streets of the old city, gleaming with the late-autumn celebration of the festival of lights so prevalent in these parts. The smell of sweets laid open under cloth canopies cloaked with the aroma of oil burning in small clay lamps to create an uniquely appetizing journey. His temporary accommodation was very close to the old city, much to his delight. In those first weeks of November 1910, Rakhal added the love for sweets to his passion for history. At the Survey, he also became acquainted with many who did not care much for either. There was Coomaraswami, a small quiet man with a sharp wit, who worked in the preservation of manuscripts, but who was really interested in becoming a civil servant. There was Rai Bahadur Daya Ram Sahni, whose impressive knowledge of architecture was surpassed by his grand wealth, and his ability to remain humble in spite of both. And there was Kripal Singh, head of the transport section, with a mysterious smile that disappeared as quickly as he did when on assignment.

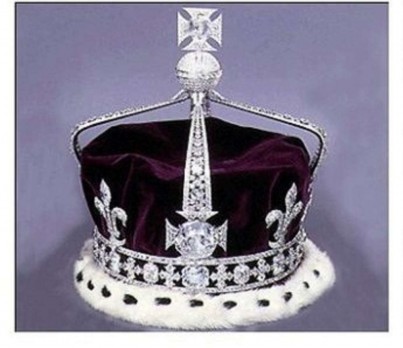

Rakhal spent considerable time filling his heart with the sights around Delhi. He was amazed by the magnificent sandstone edifice of Lal Qila (Red Fort), though the supposedly 5000 year old Purana Qila (Old Fort) a few miles down the road was no less intriguing. Unfortunately none of his colleagues shared the same curiosities as he did. His superior officer was somewhat of an exception. Sir John was an affable man, much younger than Rakhal had ever imagined, He had an intuitive understanding of those who worked under him, and had thus won Rakhal over by offering a dream assignment: document the Treaty of Lahore of 1846. The treaty was penned at the end of the first Anglo-Sikh war and was most notable for declaring the terms for transfer of the Koh-i-noor diamond from Maharaja Ranjit Singh of Punjab to Queen Victoria of England. The diamond had been a part of the crown jewels since. The original treaty of Lahore had been obtained by the Survey from London and other accessory documents had not been completely searched or filed. The Gurmukhi, Farsi and English letters in the sixty year old treaty scripts kept Rakhal occupied for the rest of the year and before long winter had given way to spring. In addition to the change in seasons, Rakhal’s colleagues noticed a change in him as well. The Rai Bahadur was first to feel something was amiss when the young Bengali did not quite care about the sweets that had been made by special order at his mansion. Coomaraswami realized that Banerji (as he called Rakhal) was no longer interested in bantering about the uselessness of serving as a civil servant. And Kripal Singh, was disappointed and even annoyed at not receiving the usual allowance from Rakhal babu. The usually boisterous and cheerful Rakhaldas had quite mysteriously been transformed into a recluse, with only the occasional journey to the old city momentarily bringing back his old self. Only Sir John knew something deeper was at work here. Finally, on a bright spring day of 1911, about a month or so after being afflicted by the mysterious disease, Rakhal was requested to have tea with Sir John in the quiet of the latter’s office. Also present on the occasion (and on many previous occasions unknown to Rakhal) was Edward Wood, aide to Lord Minto, the Viceroy of India. Rakhal did not mind Minto as much as his predecessor Lord Curzon and was generally unperturbed by the idea of having tea with the Viceroy’s aide. Sir John was not one to overtly dramatize such matters either. “Edward, Mr. Banerji here has been working on the Treaty of Lahore papers since November last,” said Sir John not a moment after taking his second sip. Edward Wood had served as a member of parliament and generally knew when to speak favorably of those he would otherwise consider disagreeable. On this occasion he mumbled something about his positive experiences with another Bengali. “I believe he has found some discrepancies in the papers, that he may want to elaborate on at some point,” continued Sir John much to Rakhal’s bewilderment. By the end of the informal meeting, Rakhal felt a deep sense of duty to share his predicament with Sir John. After Edward Wood had departed, Rakhal opened a sheet of paper from a portfolio he had been carrying all throughout, and laid it out on Sir John’s desk. The sheet was really a sliver of old reed-paper with silk embroidery on its two lateral sides. The fourth side had quite clearly been robbed of the silk border and possibly more paper too, while the fate of the border on the third side was unclear. Sir John bent over to take a closer look at the sentences written in Farsi with pale-blue Indian ink.

برای کسی که غنی و حکومت این سرزمین

یک کوه ، من نور

It became apparent that Rakhal had translated the sentence numerous times as he spoke aloud and jotted down the English phrase on another sheet:

For he who enriched and ruled this land

One Koh-i-noor

The paper had been cut or torn off below the second sentence. Rakhal continued speaking. “There are a couple of odd features about this sheet, Sir John. I found this along with the other terms of transfer that are part of the papers obtained from London. Firstly, the document supposedly signed by Maharaja Ranjit Singh was written in English and Gurmukhi, but certainly not in Farsi, as none of the parties involved therein had anything to do with Farsi. Secondly, the paper is cut below the second phrase and makes it impossible to judge the exact meaning of this couplet if at all, but I cannot but help wonder if your silence is due to the possible mention of a second Koh-i-noor.” Finally Sir John woke from his reverie, “Do you know what this means?” he asked. “I have two possibilities Sir John. But before I disclose those I would like your assurance for complete secrecy. I would also like full access to the Red Fort here in Delhi.” Rakhal had rarely seen Sir John so bewildered. “The Red Fort? Why in the world would you want to go there?”

Rakhal took out another sheet of paper and placed it beside the first one. The second sheet was obviously more modern, in fact ones used by the Survey officers for taking notes. Scribbled on this second sheet were the following Farsi phrases and their English translations:

برای او که فوت در ندای موذن For he who died at the call of the muezzin

یک مقبره One tomb

برای پیرو سلیم For the follower of Chisti

یک ملت One nation

برای او که غنی شده و اداره این سرزمین For he who enriched and ruled this land

یک کوه ، من نور One Koh-i-noor

“I got this from an inscription apparently present in the Diwan-i-khas at Red Fort from the notes of the painter William Carpenter in 1856,“ said Rakhal. Sir John nodded in agreement, William Carpenter was the foremost watercolor painter in India in the 1850s and had painted the last Kings of Delhi before the Sepoy Mutiny of 1857. “The phrases in this note clearly allude to the famous Mughal emperors, Humayun (died at the call of the muezzin by falling down a steep set of stairs), Akbar (follower of Salim Chisti) and Shah Jahan (one who enriched and ruled this land)”, continued Rakhal.

“I believe the note that I obtained by way of the Treaty of Lahore papers was really sent by someone close to the last Mughal emperor of India, Bahadur Shah Zafar…maybe the king himself. The contempt Bahadur Shah had for the British empire is well known, and in that respect he and Raja Ranjit Singh were closer than most people even today would expect. Is it that fantastic to imagine Bahadur Shah making a last ditch effort to retain a symbol of supremacy and nation-hood the Mughals had come to represent? And is it any more fantastic to imagine that the Koh-i-noor supposedly part of the crown jewels is only a fake.” This time Sir John could not keep his natural English sensibilities quiet, “that sounds most ridiculous Mr. Banerji, especially as you have no way of proving it now.” Rakhaldas was unflappable, “Sir John, all I ask is for access and help with surveying the Diwan-i-khas. Not that I expect the Koh-i-noor to be buried under a marble column there. But then again, would it be that surprising if it did?” The next morning, Sir John requested Rakhal for a meeting in his office. This time in addition to Edward Wood, there was another gentleman, a native. His stout gait gave away his identity as a soldier. And his ribbons distinguished him as a decorated one in the imperial army. “How do you do Sir”, the man greeted Rakhal in crisp English most certainly acquired in a military college. “Major General Malik Umar Hayat Khan”, introduced Sir John and continued, “an honorary aide to His Majesty King George V. And he is ceremonial head of duties at the soon to be held Delhi Durbar in December of this year. He will help you in your surveys around the city.” Rakhal was relieved to hear that Edward Wood had been kept in the dark about the specifics of his request. The man was a politician, and wont to the ills of that ilk, he thought. The Major General was a soldier, most certainly more honorable, and more importantly a native of the land.

and in that respect he and Raja Ranjit Singh were closer than most people even today would expect. Is it that fantastic to imagine Bahadur Shah making a last ditch effort to retain a symbol of supremacy and nation-hood the Mughals had come to represent? And is it any more fantastic to imagine that the Koh-i-noor supposedly part of the crown jewels is only a fake.” This time Sir John could not keep his natural English sensibilities quiet, “that sounds most ridiculous Mr. Banerji, especially as you have no way of proving it now.” Rakhaldas was unflappable, “Sir John, all I ask is for access and help with surveying the Diwan-i-khas. Not that I expect the Koh-i-noor to be buried under a marble column there. But then again, would it be that surprising if it did?” The next morning, Sir John requested Rakhal for a meeting in his office. This time in addition to Edward Wood, there was another gentleman, a native. His stout gait gave away his identity as a soldier. And his ribbons distinguished him as a decorated one in the imperial army. “How do you do Sir”, the man greeted Rakhal in crisp English most certainly acquired in a military college. “Major General Malik Umar Hayat Khan”, introduced Sir John and continued, “an honorary aide to His Majesty King George V. And he is ceremonial head of duties at the soon to be held Delhi Durbar in December of this year. He will help you in your surveys around the city.” Rakhal was relieved to hear that Edward Wood had been kept in the dark about the specifics of his request. The man was a politician, and wont to the ills of that ilk, he thought. The Major General was a soldier, most certainly more honorable, and more importantly a native of the land.

Over the next few months, Rakhaldas and his colleagues scanned the monuments within the Red Fort with a fine tooth comb. Rai Bahadur Daya Ram Sahni was perplexed and often confused about the mission. Coomaraswami treated the adventure as a fancy of his superiors, which included Rakhal too. The sweltering heat of northern India made the long hours of work a challenge for the civilians. Only the Major General was unaffected. He would customarily lead the group into the Fort every day, keep away curious onlookers and soldiers alike, and commanded a respect which even the Rai Bahadur found hard to deny. Some days were spent scrubbing pillars, and removing dirt and rocks from the exterior façades of various structures within the Fort. Others were spent studying the soil around the monuments. Only Rakhal knew what they were looking for, the inscription to match the Carpenter notes; as also the slip of paper from the Treaty of Lahore. It was the Rai Bahadur who made the accidental discovery on a balmy day in August. He had just stretched out under the marble canopy of the Diwan-i-khas, feeling fortunate to be resting in this meeting room for kings, when he noticed a small circular piece of marble engraved onto the ceiling in one quadrant, remarkable for its workmanship but even more remarkable for its absence from anywhere else in the building. The Rai Bahadur’s shouts of joy awoke everyone else from their mid-afternoon slumber. His perceived objective of this strange expedition: “to discover any irregularities in architecture within the Fort” had been achieved. Rakhaldas graciously congratulated his colleague on the discovery, and by evening the small workforce had gathered its tools and made its way back to the Survey offices to plan the next course of action. The next day Rakhal was surprised to hear that the Rai Bahadur and Coomaraswami had been transferred to the Indian museum in Calcutta. Both were in high spirits, pleased to be given coveted positions, as Assistants to the Archaeological Section of the museum, positions that had never before been occupied by natives. That evening Sir John called Rakhal to his office. For the first time in his memory Rakhal could not read Sir John’s mind. “I have helped you this far Mr. Banerji, but you will have to go alone the rest of the way. For if your original premise regarding the famous gem is true, the soon to be emperor of India would be greatly embarrassed. Which reminds me,” he continued in the same detached manner, “the Delhi Durbar is to be held in December, the capital is to be shifted then as well, lord almighty knows what will become of the ancient monuments, but the Survey will most definitely not gain easy access as before.” Rakhal realized the daunting task ahead, and the little time he had to accomplish it.

Over the next few months, Rakhaldas and his colleagues scanned the monuments within the Red Fort with a fine tooth comb. Rai Bahadur Daya Ram Sahni was perplexed and often confused about the mission. Coomaraswami treated the adventure as a fancy of his superiors, which included Rakhal too. The sweltering heat of northern India made the long hours of work a challenge for the civilians. Only the Major General was unaffected. He would customarily lead the group into the Fort every day, keep away curious onlookers and soldiers alike, and commanded a respect which even the Rai Bahadur found hard to deny. Some days were spent scrubbing pillars, and removing dirt and rocks from the exterior façades of various structures within the Fort. Others were spent studying the soil around the monuments. Only Rakhal knew what they were looking for, the inscription to match the Carpenter notes; as also the slip of paper from the Treaty of Lahore. It was the Rai Bahadur who made the accidental discovery on a balmy day in August. He had just stretched out under the marble canopy of the Diwan-i-khas, feeling fortunate to be resting in this meeting room for kings, when he noticed a small circular piece of marble engraved onto the ceiling in one quadrant, remarkable for its workmanship but even more remarkable for its absence from anywhere else in the building. The Rai Bahadur’s shouts of joy awoke everyone else from their mid-afternoon slumber. His perceived objective of this strange expedition: “to discover any irregularities in architecture within the Fort” had been achieved. Rakhaldas graciously congratulated his colleague on the discovery, and by evening the small workforce had gathered its tools and made its way back to the Survey offices to plan the next course of action. The next day Rakhal was surprised to hear that the Rai Bahadur and Coomaraswami had been transferred to the Indian museum in Calcutta. Both were in high spirits, pleased to be given coveted positions, as Assistants to the Archaeological Section of the museum, positions that had never before been occupied by natives. That evening Sir John called Rakhal to his office. For the first time in his memory Rakhal could not read Sir John’s mind. “I have helped you this far Mr. Banerji, but you will have to go alone the rest of the way. For if your original premise regarding the famous gem is true, the soon to be emperor of India would be greatly embarrassed. Which reminds me,” he continued in the same detached manner, “the Delhi Durbar is to be held in December, the capital is to be shifted then as well, lord almighty knows what will become of the ancient monuments, but the Survey will most definitely not gain easy access as before.” Rakhal realized the daunting task ahead, and the little time he had to accomplish it.

His first job was to clean the marble panel that had been discovered. The panel was stuck to the ceiling, almost 20 ft. high. It would be impossible to work alone during the day and not attract attention. His only chance was under the cover of darkness. So, when the bustle of Chawri Bazaar had subsided, and the evening azaan from Jama Masjid had echoed many times against the stone and marble of the Fort, when the soldiers guarding the Lahore Gate had wandered off for their nightly smoke and drink, two figures would make their way hurriedly to the Diwan-i-khas. The Major General had always known about Rakhal’s quest. This was Sir John’s way of balancing loyalty, to his profession and to the King of England. The two men carried with them ladders and tools, for Rakhal to set about working, scrubbing, cleaning and polishing the marble slab on the ceiling. He would return many times later in the day, as an unsuspecting tourist, and survey the progress made during the previous night. It took a mere fortnight for the discovery to be confirmed! The timing could not have been more perfect. The shift of the capital of the British Raj from Calcutta to Delhi was only two weeks away. The Delhi Durbar to crown King George V, Emperor of India was to be held shortly thereafter. And hidden under the ceiling of the Diwan-i-khas was described the possible whereabouts of the Koh-i-noor.

All throughout Sir John had kept tabs on Rakhal’s progress, but could not think of a satisfactory plan for announcing the discovery. The complication was this: the inscription on the ceiling , made in a circular fashion, comprised the exact same phrases as in the Carpenter notes, but nothing more and neither Rakhal nor Sir John were none too wiser about the whereabouts of the priceless gem. Now, even Rakhal could not help but doubt the idiocy of an alliance between Ranjit Singh and Bahadur Shah. And so on a chilly late November evening, Rakhaldas Bandyopadhyay received an invitation for dinner from Sir John Marshall, to celebrate the impending birth of a new capital of the British Raj the next day. Edward Wood was present as were notable other ministers and bureaucrats. While brooding over some scotch, he heard Wood boast eloquently about being part of the festivities. “I will,” he started, “visit the Coronation Park, “the Emperor and I will.” For a moment Rakhal could not feel the earth underneath him, a lamp had suddenly been lit in some far place and he had to ensure it would not be extinguished again. “There it was right before my eyes all this while”, he thought, “the phrases arranged in circular fashion.” He rushed out from Sir John’s residence and reached a street-lamp, pulling out a scrap of paper and furiously jotted down the translation of the Carpenter phrases. After a while, he stared long and hard at his effort:

One Tomb, For the Follower of Chisti

One Nation, For he who enriched and ruled this land

One Koh-i-noor, For he who died at the call of the muezzin

The third phrase was not meant to state a historical fact at all. It was a possible directive, an indication to the whereabouts of the gem and not very hard to understand either. Humayun’s tomb was a few miles down the road from the Red Fort, and was known to be a hiding place for Bahadur Shah during the Sepoy mutiny of 1857. What better place to hide a gem, right here in the capital city, in a tomb relatively inconspicuous, compared off course to the Red Fort. Rakhal had to get there tonight itself, as the imperial army was marching into town and was already camping at all the older monuments including the Old Fort. “Kripal-jee”, he called out to the coach driver, “quick, we have no time to waste. You must take me as fast as your horses will to Humayun-ka-muqbara”. Kripal Singh was never one to disobey orders. The carriage flew down streets lined by the bureaucrat’s houses, some of them wondering whether the horses had gone mad. As their carriage passed the looming exterior of the Old Fort, Rakhal’s heart raced even more. “Faster, Kripal Singh,” Rakhal could not contain himself any longer. As the carriage passed the Nila Gumbaj next to the dargah of Nizamuddin Aulia, Rakhal’s heart sunk. There lined up in front of them was a vast sea of humanity, the King’s army, all ten thousand of them, camped out and under trees, under the sandstone entrance to the tomb, and all around. Before the carriage could reach the gate, five mounted soldiers came rushing in. “Janaab, this gentleman here is very learned,” said Kripal, “he has some business in the tomb.” The soldiers laughed heartily at this comic show of drunken fervor. Before Kripal Singh could say something more, Rakhal pulled him back. He realized it was futile to go in now. Probably at some later date. As the carriage turned back, Rakhal quietly watched the soldiers and officers making arrangements for the night. “No one has a clue”, Rakhal thought, “of the symbol buried somewhere in this land, a symbol of an ancient land…none beholden to any crown or empire.” (to be continued)

The third phrase was not meant to state a historical fact at all. It was a possible directive, an indication to the whereabouts of the gem and not very hard to understand either. Humayun’s tomb was a few miles down the road from the Red Fort, and was known to be a hiding place for Bahadur Shah during the Sepoy mutiny of 1857. What better place to hide a gem, right here in the capital city, in a tomb relatively inconspicuous, compared off course to the Red Fort. Rakhal had to get there tonight itself, as the imperial army was marching into town and was already camping at all the older monuments including the Old Fort. “Kripal-jee”, he called out to the coach driver, “quick, we have no time to waste. You must take me as fast as your horses will to Humayun-ka-muqbara”. Kripal Singh was never one to disobey orders. The carriage flew down streets lined by the bureaucrat’s houses, some of them wondering whether the horses had gone mad. As their carriage passed the looming exterior of the Old Fort, Rakhal’s heart raced even more. “Faster, Kripal Singh,” Rakhal could not contain himself any longer. As the carriage passed the Nila Gumbaj next to the dargah of Nizamuddin Aulia, Rakhal’s heart sunk. There lined up in front of them was a vast sea of humanity, the King’s army, all ten thousand of them, camped out and under trees, under the sandstone entrance to the tomb, and all around. Before the carriage could reach the gate, five mounted soldiers came rushing in. “Janaab, this gentleman here is very learned,” said Kripal, “he has some business in the tomb.” The soldiers laughed heartily at this comic show of drunken fervor. Before Kripal Singh could say something more, Rakhal pulled him back. He realized it was futile to go in now. Probably at some later date. As the carriage turned back, Rakhal quietly watched the soldiers and officers making arrangements for the night. “No one has a clue”, Rakhal thought, “of the symbol buried somewhere in this land, a symbol of an ancient land…none beholden to any crown or empire.” (to be continued)

Footnote: Sir John Marshall served as the director general of the Archaeological Survey of India till 1928. He spearheaded the excavations that led to the discovery of Harappa and Mohenjo-Daro, two cities that formed the basis of the Indus Valley Civilization. Rakhaldas Bandyopadhyay was instrumental in discovery of Mohenjo-Daro while Rai Bahadur Daya Ram Sahni led the discovery at Harappa. Major General Malik Umar Hayat Khan (later knighted) served as Assistant Delhi Herald of Arms Extraordinary at the Delhi Durbar of 1911. Edward Wood (as Lord Irvine) served as Viceroy of India between 1925-1934. The Koh-i-noor has been a part of the British Crown Jewels since 1849.

This story series is a work of fiction.